1: Introduction to Public Health Nutrition

Provide the definition of public health nutrition (

PHN ) given by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Public Health Nutrition Task Force in 2012.Explain five key roles of a public health nutritionist within a public health agency.

Describe the Social-Ecological Model and how it can be used by public health nutritionists to understand the multiple levels of influence on nutrition- and other health-related behaviors.

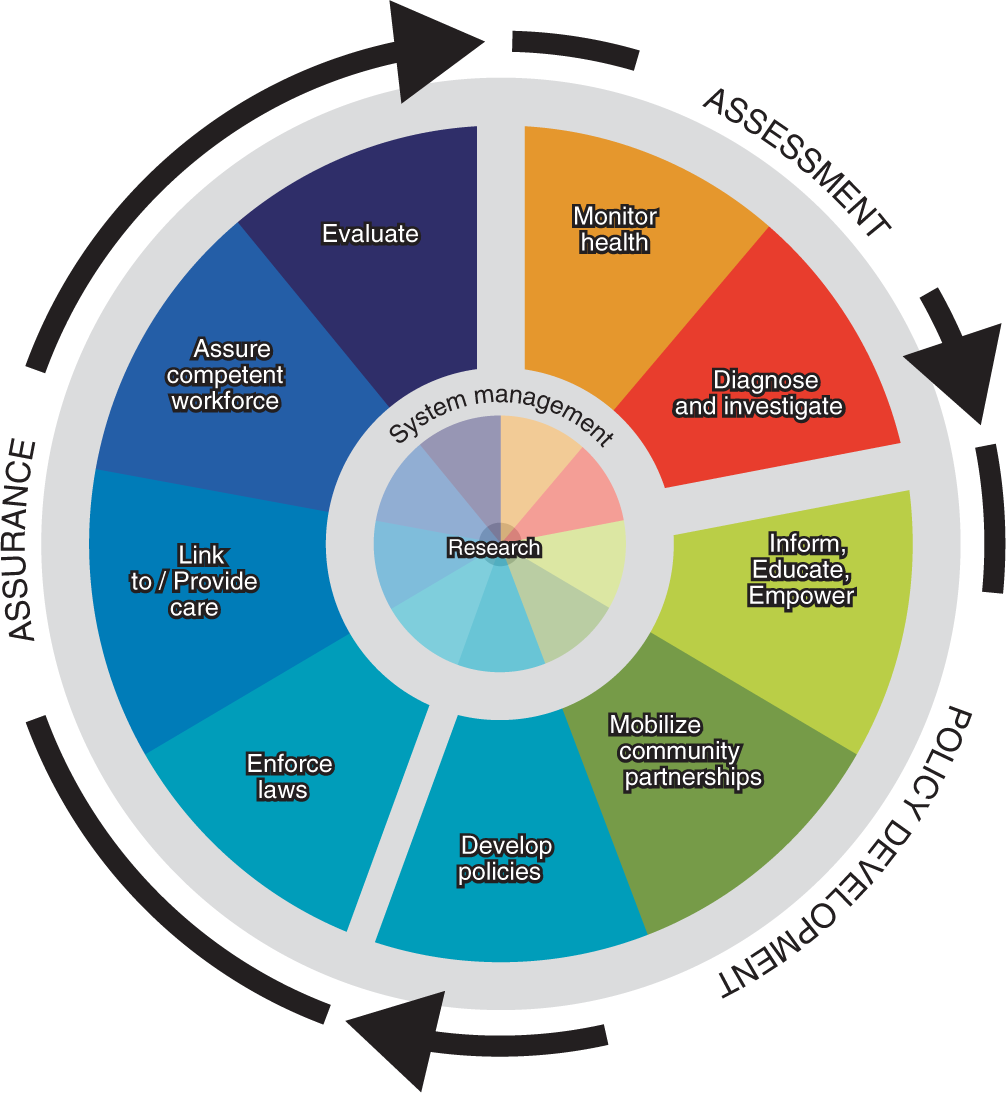

Describe the core functions of public health including assessment, assurance, and policy development.

List the 10 essential public health services and 16 essential public health nutrition services that support these core functions.

Describe essential areas of training for public health nutritionists, including advanced training in nutrition and public health, knowledge of current nutrition-related evidence-based skills, and the core functions of public health.

INTRODUCTION

History of PHN in the United States

Mary Egan,1 a leader in shaping contemporary

Source: From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Public Health System. 2018, June. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html

During the 1950s, growth of the profession became more organized with the establishment of the Association of Faculties of Graduate Programs in Public Health Nutrition (currently, the Association of Graduate Programs in Public Health Nutrition)6 in 1950 and the Association of State and Territorial Public Health Nutrition Directors (currently, the Association of State Public Health Nutritionists) in 1952. In the mid-1960s, legislation passed to reduce poverty in the United States provided funding for projects like the Maternity and Infant Care Program, the Compressive Health Projects for Children and Youth, Head Start, and the Medicare and Medicaid programs. These programs opened many more positions for public health nutritionists as practitioners in the programs or as consultants. The 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health suggested actions to reduce malnutrition and hunger.7 One of the recommendations was to provide nutrition services to pregnant women, infants, and young children from impoverished households. In 1972, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (

In the 1970s and 1980s, several landmark documents were released that focused on the importance of nutrition in the prevention of chronic diseases and to provide dietary guidance for the U.S. population. First, in 1977, the Dietary Goals for the United States12 were released, followed by Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in 1979,13 which outlined the first set of national health goals and objectives that focused on health promotion and disease prevention and highlighted the role of nutrition in these areas. The next year, two important documents were released. First, Promoting Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation was released13 and included 226 health-related objectives and action steps for improving population health over the next decade. These documents were the forerunners for the Healthy People series of documents,14 which are science-based health objectives for the U.S. population that are released every 10 years. The second landmark document released that year was Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans.15 This was the first edition of dietary guidance for the U.S. population that focused on healthful dietary patterns based on the most accurate scientific evidence at the time.16

During the past two decades of the 1900s, as scientific understanding of chronic diseases and their relationship to nutrition continued to develop, public health nutritionists began working across the life course in the areas of health promotion and disease prevention. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (

The Healthy People14 series of national health objectives began with Healthy People 2000,22 released September 1990. Since the introduction of these national health objectives, major progress has been made in the reduction of preventable illness and death, including nutrition-related diseases, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, along with risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia.23 However, there is much work to be done still. Two nutrition-related leading health indicators, “reduce the proportion of adults who are obese” and “reduce the proportion of children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years who are considered obese,” have not met the 2020 targets and have actually increased from 33.9% to 38.6% and 16.1% to 17.8%, respectively. Healthy People 2020 objectives related to dietary intake need improvement as well. Although these objectives have improved from baseline, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (

Source: From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 10 Essential Public Health Services. 2018, June. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html

GLOBAL PHN

Global

| PUBLIC HEALTH CORE FUNCTION(S) | ESSENTIAL PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITION SERVICES |

|---|---|

| Assessment | Assessing the nutritional status of specific populations or geographic areas |

| Identifying priority populations that may be at nutritional risk | |

| Initiating and participating in nutrition data collection | |

| Policy development | Providing leadership in the development of and planning for health and nutrition policies |

| Raising awareness among key policy-makers on the potential impact of nutrition and food regulations on budget decisions on the health of the community | |

| Acting as an advocate for priority populations on food and nutrition issues | |

| Assurance | Planning for nutrition services in conjunction with other health services, based on information obtained from an adequate and ongoing database focused on health outcomes |

| Recommending and providing specific training and programs to meet identified nutrition needs | |

| Identifying or assisting in development of accurate, up-to-date nutrition education materials | |

| Ensuring the availability of quality nutrition services to priority populations, including nutrition screening, assessment, education, counseling, and referral for food assistance and follow-up | |

| Providing community health promotion and disease prevention activities that are population-based | |

| Providing quality assurance guidelines for practitioners dealing with food and nutrition issues | |

| Facilitating coordination with other providers of health and nutrition services within the community | |

| Assessment/Assurance/Policy development | Participating in nutrition research, demonstration, and evaluation projects |

| Providing expert nutrition consultation to the community | |

| Evaluating the impact of the health status of populations who receive public health nutrition services |

Sources: From Probert K. Moving to the Future: Developing Community-Based Nutrition Services. Washington, DC: Association of State and Territorial Public Health Nutrition Directors; 1996; Institute of Medicine Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218224

Foundational Principles

Health and well-being of all people and communities are essential to a thriving, equitable society.

Promoting health and well-being and preventing disease are linked efforts that encompass physical, mental, and social health dimensions.

Investing to achieve the full potential for health and well-being for all provides valuable benefits to society.

Achieving health and well-being requires eliminating health disparities, achieving health equity, and attaining health literacy.

Healthy physical, social, and economic environments strengthen the potential to achieve health and well-being.

Promoting and achieving the nation’s health and well-being is a shared responsibility that is distributed across the national, state, tribal, and community levels, including the public, private, and not-for-profit sectors.

Working to attain the full potential for health and well-being of the population is a component of decision-making and policy formulation across all sectors.

Overarching Goals

Attain healthy, thriving lives and well-being, free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death.

Eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all.

Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining full potential for health and well-being for all.

Promote healthy development, healthy behaviors, and well-being across all life stages.

Engage leadership, key constituents, and the public across multiple sectors to take action and design policies that improve the health and well-being of all.

Plan of Action

Set national goals and measurable objectives to guide evidence-based policies, programs, and other actions to improve health and well-being.

Provide data that is accurate, timely, accessible, and can drive targeted actions to address regions and populations with poor health or at high risk for poor health in the future.

Foster impact through public and private efforts to improve health and well-being for people of all ages and the communities in which they live.

Provide tools for the public, programs, policy-makers, and others to evaluate progress toward improving health and well-being.

Share and support the implementation of evidence-based programs and policies that are replicable, scalable, and sustainable.

Report biennially on progress throughout the decade from 2020 to 2030.

Stimulate research and innovation toward meeting Healthy People 2030 goals and highlight critical research, data, and evaluation needs.

Facilitate development and availability of affordable means of health promotion, disease prevention, and treatment.

Source: From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030 Framework. 2019, November 4. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about-healthy-people/development-healthy-people-2030/framework

PHN : DEFINITIONS

Several organizations have made efforts to define

that member of the public health agency staff who is responsible for assessing community nutrition needs and planning, organizing, managing, directing, coordinating, and evaluating the nutrition component of the health agency’s services … establishes linkages with related community nutrition programs, nutrition education, food assistance, social or welfare services, child care, services to the elderly, other human services, and community-based research.32

Hughes,33 an international

In the ensuing years, definitions of

| ORGANIZATION | DATE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom Nutrition Society | 1998 | The application of nutrition and physical activity to the promotion of good health, the primary prevention of diet-related illness of groups, communities, and populations (not individuals)34 |

| Strategic Intergovernmental Nutrition Alliance (Australia) | 2001 | Focuses on issues affecting the whole population rather than the specific dietary needs of individuals The impact of food production, distribution, and consumption on the nutritional status and health of particular population groups is taken into account, together with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors in the broader community35 |

| World Public Health Nutrition Association | 2006 | The promotion and maintenance of nutrition-related health and well-being of populations through organized efforts and informed choices of society31 |

| Dietitians of Canada | 2006 | Health promotion through awareness raising, education and skill building, supportive environments and policy development, collaborations and partnerships, research and evaluation, and the mentoring and education of future nutrition and health professionals as well as other congruent descriptors29 |

| Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics | 2012 | The application of nutrition and public health principles to improve or maintain optimal health of populations and targeted groups through enhancements in programs, systems, policies, and environments28 |

Sources: From Uauy R. Understanding public health nutrition. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):309–310. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61145-3; Strategic Intergovernmental Nutrition Alliance. Eat Well Australia: An Agenda for Action for Public Health Nutrition 2000–2010. Canberra, Australia: Department Health and Aged Care; 2001; Hughes R. Workforce development: challenges for practice, professionalization and progress. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(8):765–767. doi:10.1017/S1368980008002899; Chenhall C. Public Health Nutrition Competencies: Summary of Key Informant Inte r views. Toronto, Canada: Dietitians of Canada. 2006, September. https://www.dietitians.ca/Downloads/Public/Public-Health-Nutrition-Competencies--key-informant.aspx; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Public health nutrition: it’s every member’s business.

PHN : TRAINING AND WORKFORCE

In recent years,

The

PHN : POSITIONS AND CAREER SETTINGS

Position descriptions, classifications, educational requirements, and career settings for

Source: Data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines. The Social-Ecological Model. 2015. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/chapter-3/social-ecological-model; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Social Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. 2019, January. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html; World Health Organization. Violence Prevention Alliance. The Ecological Framework. 2019. https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/ecology/en.; Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(7):513–531. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,47 career growth in nutrition and dietetics is projected to increase over the next decade by 11%, which is higher than growth in many other professions. Job growth in

PHN : FUTURE TRENDS

In 2006, the World Congress of

Because current

Currently,

Another key area of future focus for the

Closely aligned with leadership development, developing skilled mentors will also be key to increasing the capacity of the

CONCLUSION

KEY CONCEPTS

Public health nutrition, as defined by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Public Health Nutrition Task Force is, “the application of nutrition and public health principles to improve or maintain optimal health of populations and targeted groups through enhancements in programs, systems, policies, and environments”.28

Public health nutritionist, as defined my Margaret Kaufman, is “that member of the public health agency staff who is responsible for assessing community nutrition needs and planning, organizing, managing, directing, coordinating, and evaluating the nutrition component of the health agency’s services … establishes linkages with related community nutrition programs, nutrition education, food assistance, social or welfare services, child care, services to the elderly, other human services, and community-based research”.32

The Social-Ecological Model can be used by public health nutritionists to help them understand the multiple levels of influence on nutrition- and other health-related behaviors. The spheres of influence include:

The individual level, which encompasses age, sex, literacy level, race and ethnicity, food preferences, acute childhood traumas, and more

The interpersonal level, which includes families, friends, social networks, coworkers, and peers

The organizational level, which includes worksites, parks and recreation facilities, early childhood education settings, schools, colleges and universities, and community organizations

Sectors, including governmental, educational, healthcare, transportation, public health, community, and business sectors

Societal and policy levels, such as traditions, beliefs, religions, policies and laws, societal changes, and economic safety nets

The core functions of public health are assessment, assurance, and policy development. There are 10 essential public health services and 16 essential

PHN services that support these core functions.Public health nutritionists should have advanced training in nutrition and public health to develop knowledge of current nutrition-related evidence-based skills related to the core functions of public health and the essential health services of public health and

PHN .

CASE STUDY: A PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITIONIST’S PROCESS FOR INCREASING ACCESS TO HEALTHFUL FOODS IN URBAN AND RURAL COMMUNITIES WITH MOBILE FOOD MARKETS

A public health nutritionist is working with other public health and nutrition professionals on a state coalition to increase access to healthful foods in urban and rural communities. The team begins by assessing the number and types of retail food stores across the state. After finding this information, they then look at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (

On the opening day, the mobile markets provide low-cost and no-cost healthful foods and beverages to 2,800 families (over 10,000 individuals). In addition, coalition volunteers help eligible participants enroll in

Case Study Questions

Identify at least 10 essential

PHN services described in the case study and categorize them by the associated core functions of public health.Use the Economic Research Service Food Access Research Atlas to find your home county and determine if there are low-income, low-access areas there.

In what other areas could the coalition advocate to improve food access for the priority communities?

SUGGESTED LEARNING ACTIVITIES

Explore the Association of State Public Health Nutrition website (www.asphn.org) and complete the following:

List the association’s mission and vision.

Describe at least two committees or councils in the association.

List one way you could become involved in the association.

Visit the

SNAP website (www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program) and find the following:Based on the website, provide a brief description of

SNAP in your own words.What are the eligibility requirements for

SNAP ?What can be purchased with

SNAP benefits?

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Discuss why it is important for public health nutritionists to have advanced training in both nutrition and public health?

This chapter lists several definitions of

PHN ; compare and contrast these definitions by discussing the commonalities and differences among them.Describe at least five ways that public health nutritionists can work with other public health professionals to improve population health.

List and describe at least five historical milestone events and/or legislation that led to expanded roles of public health nutritionists in the United States.

Describe the purpose of the World Public Health Nutrition Association.

CONTINUE YOUR LEARNING RESOURCES

American Public Health Association Food and Nutrition Section. https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/food-and-nutrition/who-we-are

Association of Graduate Programs in Public Health Nutrition. www.agpphn.org

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/index.htm

Healthy People 2030. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/Development-Healthy-People-2030/Framework

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Public Health/Community Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group. https://www.phcnpg.org/page/about

U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. https://www.usda.gov/topics/food-and-nutrition

GLOSSARY

Association of Graduate Programs in Public Health Nutrition:

One of the first formalized organizations for the profession, created in 1950.

Association of State Public Health Nutritionists:

One of the first formalized organizations for the profession, created in 1952.

Evidence-based:

Practice that relies on scientific evidence for decision-making and informing practice.

Food and Drug Act:

Passed by Congress in 1906 to begin oversight of food production, sales, and labeling.

Global

Developed, transitioning, and developing countries have their own unique histories related to the foundations of public health and growth of

Healthy People:

Series of documents that are science-based health objectives for the U.S. population, released every 10 years.

Key descriptors to define

Solution-oriented, social and cultural aspects, advocacy, disease prevention, and interventions based on systems, communities, and organizations.

Mary Egan:

Leader in shaping contemporary

Moving to the Future: Developing Community-Based Nutrition Services:

Text providing the delineation of the essential

Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans:

Hallmark document providing dietary guidance for the U.S. population that focused on healthful dietary patterns.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act:

Legislation that underscores the need for primary prevention as well as screening and treatment of chronic diseases; passed in 2010.

Public health nutritionist:

A member of the public health agency staff responsible for assessing community nutrition needs and planning, organizing, managing, directing, coordinating, and evaluating the nutrition component of the health agency’s services.

Social determinants of health:

Behavioral, environmental, biological, societal, and economic factors that influence individual and population health.

Social-Ecological Model:

Key model for application by public health nutritionists to understand how behavioral, societal, and economic factors influence health.

Social Security Act:

Legislation that influenced public health infrastructure and subsequent growth of

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (

One of the first programs to provide nutrition services to pregnant women, infants, and children, established in 1972.

The Future of Public Health:

Groundbreaking document outlining the three core functions of public health—assessment, policy development, and assurance—and the 10 essential services of public health, released by the

White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children:

First conference, held in 1909, by the White House related to

World Health Organization (

Created in 1948 as part of the United Nations, formed to combat communicable diseases and to improve maternal, infant, and child health and nutrition.

World Public Health Nutrition Association:

First international organization to promote and improve

REFERENCES

- 1.Egan M. Public health nutrition: a historical perspective. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(3):298–304. doi:10.1016/0002-8223(94)90372-7

- 2.Winslow CEA. The Evolution and Significance of the Modern Public Health Campaign. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1923.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Public Health System. 2018, June. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html

- 4.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218224

- 5.Michael J, Goldstein M. Reviving the White House Conference on Children. Children’s Voice. 2008;17(1). https://www.cwla.org/reviving-the-white-house-conference-on-children

- 6.Association of Graduate Programs in Public Health Nutrition. Directory. 2019, October. https://agpphn.org/directory

- 7.. White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health, 1970. https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/27/9/247/1875780

- 8.National WIC Association. WIC Program Overview and History. https://www.nwica.org/overview-and-history

- 9.Owen GM, Kram KM, Garry PJ, et al. A study of nutritional status of preschool children in the United States, 1968-1970. Pediatrics. 1974;52(suppl):597–646.

- 10.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten-state nutrition survey, 1968-1970. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Publication no. HSM 72-8134; 1972.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. History. 2015, November 6. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/history.htm

- 12.U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs. Dietary Goals for the United States. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1977.

- 13.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Year 2000 national health objectives. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38(37):629–633.

- 14.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People. 2019, November 4. https://www.healthypeople.gov

- 15.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Home and Garden Bulletin No. 232; 1980. https://pubs.nal.usda.gov/sites/pubs.nal.usda.gov/files/hgb.htm#nbr220

- 16.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Dietary Guidelines Committee. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 1995, to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. Appendix I: History of Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 1995. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga95/12DIETAP.HTM

- 17.Remington PL, Brownson RC. Fifty years of progress in chronic disease epidemiology and control. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):70–77.

- 18.Haughton B, Story M, Keir B. Profile of public health nutrition personnel: challenges for population/system-focused roles and state-level monitoring. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98(6):664–670.

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 10 Essential Public Health Services. 2018, June. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html

- 20.Probert K. Moving to the Future: Developing Community-Based Nutrition Services. Washington, DC: Association of State and Territorial Public Health Nutrition Directors; 1996.

- 21.Hughes R, Begley A, Yeatman H. Consensus on the core functions of the public health nutrition workforce in Australia. Nutr Diet. 2016;73(1):103–111.

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. History and Development of Healthy People. 2019, November 4. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/History-Development-Healthy-People-2020

- 23.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicators: Progress Update. 2019, November 4. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/Healthy-People-2020-Leading-Health-Indicators%3A-Progress-Update

- 24.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030 Framework. 2019, November 4. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about-healthy-people/development-healthy-people-2030/framework

- 25.Fielding JE. Public health in the twentieth century: Advances and challenges. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20(1):xiii–xxx. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.0

- 26.Schmidt H. Chronic disease prevention and health promotion. In: Barrett DH, Ortmann LH, Dawson A, et al. eds. Public Health Ethics: Cases Spanning the Globe. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435779

- 27.

- 28.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Public Health Nutrition: It’s Every Member’s Business. HOD Backgrounder. 2012. https://www.eatrightpro.org/-/media/eatrightpro-files/leadership/hod/mega-issues/backgrounders/09-public-health-nutrition-backgrounder.pdf?la=en&hash=06B0F66D994A6BA0C574AB9A27FBA4A155AFD428

- 29.Chenhall C. Public Health Nutrition Competencies: Summary of Key Informant Interviews. Dietitians of Canada. 2006, September. https://www.dietitians.ca/Downloads/Public/Public-Health-Nutrition-Comptencies--key-informant.aspx

- 30.Hughes R. Competencies for effective public health nutrition practice: a developing consensus. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(5):683–691.

- 31.Hughes R. Workforce development: challenges for practice, professionalization and progress. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(8):765–767. doi:10.1017/S1368980008002899

- 32.Kaufman M, ed. Personnel in Public Health Nutrition for the 1980’s. McLean, VA: Association of State and Territorial Health Officials Foundation; 1982.

- 33.Hughes R. Definitions for public health nutrition: a developing consensus. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(6):615–620. doi:10.1079/PHN2003487

- 34.Uauy R. Understanding public health nutrition. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):309–310. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61145-3

- 35.Strategic Intergovernmental Nutrition Alliance. Eat Well Australia: An Agenda for Action for Public Health Nutrition 2000–2010. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2001.

- 36.Rhea M, Bettles C. Future changes driving dietetics workforce supply and demand: future scan 2012-2022. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(3):S10–S24. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.008

- 37.Haughton B, Stang J. Population risk factors and trends in health care and public policy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(3):S35–S46. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.011

- 38.. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 USC §18001 (2010).

- 39.Wells EV, Sarigiannis AN, Boulton ML. Assessing integration of clinical and public health skills in preventive medicine residencies: using competency mapping. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):S107–S116. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.004

- 40.Institute of Medicine. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. doi:10.17226/10542

- 41.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward and experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(7):513–531. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- 42.Institute of Medicine. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

- 43.Spence ML, ed. Strategies for Success: Curriculum Guide (Didactic and Experiential Learning). 3rd ed. Association of Graduate Programs in Public Health Nutrition; 2013.

- 44.Dodds JM. Personnel in Public Health Nutrition for the 2000s. Tucson, AZ: Association of State Public Health Nutritionists; 2009. https://www.asphn.org/resource_files/105/105_resource_file1.pdf

- 45.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines. The Social-Ecological Model. 2015. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/chapter-3/social-ecological-model

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Social Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. 2019, January. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html

- 47.Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook, Dietitians and Nutritionists. 2019, September 4. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/dietitians-and-nutritionists.htm

- 48.Serra-Majem L. Moving forward in public health nutrition: the I World Congress of Public Health Nutrition. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(suppl 1):S2–S6. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00150.x

- 49.

- 50.Shrimpton R, Hughes R, Recine E, et al. Nutrition capacity development: a practice framework. Public Health Nutr. 2013;7(3):682–688. doi:10.1017/S1368980013001213

- 51.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Certificates of Training. Public Health Nutrition-Modules 1–5. https://www.eatrightstore.org/cpe-opportunities/certificates-of-training?pageSize=20&pageIndex=3&sortBy=namedesc

- 52.Appalachian State University. App State Online. Public Health Nutrition Practice Graduate Certificate. https://online.appstate.edu/programs/id/public-health-nutrition

- 53.National Board of Public Health Examiners. Credentialing Public Health Leaders. 2019. https://www.nbphe.org

- 54.National Commission for Health Education Credentialing, Inc. Health Education Credentialing. https://www.nchec.org/health-education-credentialing

- 55.Wright K, Rowitz L, Merkle A, et al. Competency development in public health leadership. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1202–1207. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1202

- 56.Haughton B, George A. The Public Health Nutrition workforce and its future challenges: the US experience. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(8):782–791. doi:10.1017/S1368980008001821

- 57.Palermo C, Hughes R, McCall L. An evaluation of a public health nutrition workforce development intervention for the nutrition and dietetics workforce. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23:244–253. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01069.x

- 58.World Health Organization. Violence Prevention Alliance. The ecological framework. 2019. https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/ecology/en