Chapter 1: Community-Oriented Health Services: History, Framework, Nature, and Significance

Health drives all human endeavors in that without basic health functioning, nothing much matters. It drives physical, mental, and social well-being in lived environments (World Health Organization [

Health as the interplay between environmental and individual factors is both a product of and an object of consumption by enactors of health and well-being, who are typically community members (Golden & Earp, 2012). Well-being is the subjective sense of relative health from lived health experiences, most often in the context of community (see Cumming, Mpofu, & Machina, this volume; Dluhy & Swartz, 2006). The provision and protection of population health is of such overriding importance that most developed nations commit 8% to 12% of their gross domestic product to health-related services (Taylor & George, 2014). Nonetheless, access to health care services varies across communities and individuals, largely influenced by socioeconomic conditions as well as enacted health policies and the manner in which these policies are translated into community-oriented health services (

Most commonly, community is conceptualized as a group of people who are linked by social ties to a habitat or geographic setting location, even though they may be of diverse backgrounds (MacQueen et al., 2001). According to Wilkinson (1991), three fundamental properties of a community include (a) a local ecology or an organization of social life that meets daily needs and allows for adaptation to change; (b) a comprehensive interactional structure, or social whole, that expresses a full round of human interests and needs; and (c) a bond of local solidarity represented in people acting together to solve common problems. Community is thus founded on social interactions, where individuals and groups work together toward a shared vision in a particular locality. This implies that community is not just a geographic area or place, but rather could comprise membership that is partially interconnected by demographics or other social variables that define that specific community. Notably, those interested in the development of community pay more attention to the quality of relationships among these elements, with more emphasis on the integrated economic, social, and environmental structures (Wilkinson, 1991).

Within geographic communities, a sense of community may vary widely with the lived experience of the community, and this often is mediated by differences in access to the resources for community participation, including for health. For example, Tennent and colleagues (2009) reported that sense of community influences self-reported well-being. However, people of the same geographic location may experience sense of community in different ways from lack on equity in accessing social determinants of health. Subgroups within the larger community in themselves comprise communities of interest that may be defined by sharing a common health-related condition (as with support groups) or differential access to health care compared to other typical community members (as with people with substance use needs or racial/cultural minorities). For instance, community residents from marginalized groups experience health-damaging stressors from lack of equitable access to resources for well-being with which to cope with health-related stressors. Health improvement initiatives across diverse communities need to take into account the existence of communities within communities not defined by geography (Jones & Wells, 2007) or as defined by health status. Geographic information systems and other techniques are available for use in defining the subcommunities when simple neighborhood location data alone do not suffice.

The

Public health policies should be need driven (see An, Huang, & Baghbanian, this volume). Two implications follow from this premise if true. First, the health services available and accessible may reflect provider perceptions of the demand for such services as much as health services by their availability can also explain the demand for them (Taylor & George, 2014). Second, many health needs recognized by the constituent communities may not be provided for or recognized by existing health services, thereby constraining their capacity and responsiveness to health needs and demands by community consumers. Thus, despite the apparent social good to provide for the community health needs, the practices and instruments to provide for such needs may misalign with what the community wants to access for their health needs (Taylor & George, 2014; see also Bickenbach, this volume) in the absence of direct participation by the community in determining the health outcomes they aspire.

This chapter briefly discusses the history of frameworks for understanding

History of COHS

The logic and processes of

Other significant

The Alma-Ata declaration also highlighted that people, as members of their communities, have the right and duty to engage individually and collectively in the planning and implementation of their health care, and urged governments to develop and reinforce the abilities of communities to participate in their health care planning. The 32nd assembly of the United Nations Organization (

Around the same time, the

In recent years, there has been remarkable attention and resources devoted to community-oriented approaches to public health (see Williams & Ronan, this volume), most notably from both government and nongovernment-affiliated organizations in the United States (e.g., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000, 2010). Furthermore, scholars from numerous health-related disciplines are investigating health practices using community-oriented approaches to research methods, including participatory action research, collaborative inquiry, empowerment evaluation, and community-based participatory research (

A recent systematic literature review by Las Nueces and colleagues (2012) identified relatively few published

These calls for more integrated approaches to research and practice in public health continue to be expressed in major national reports, health policy statements, and public health project initiatives (Israel et al., 1998). The growing interest in community-oriented approaches to public health has highlighted ecological approaches to research, like

Frameworks for Participatory COHS

Structurally, communities are complex entities in their composition and health-related needs and demands. They also vary in their civic competencies or their ability to engage in collective action for community improvement (Cottrell, 1976). Civic competencies presume civic infrastructure or the community improvement forums to identity, prioritize, coordinate, and implement pro-community initiatives, inclusive of those for community health. Community competence copes with the challenges of collective living, consensus-driven civic action through both formal and informal networks, and coalitions for the common good, civic health, or the direct and meaningful participation of the community in decisions that affect their health. Community action theory (see Butterfoss, Goodman, & Wandersman, 1993; Lasker & Weiss, 2003) speaks to the civic infrastructure for communities engaged in civic health. The

Community Coalition Action Theory

Every community engaged in some form of collective action which defines it as community (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2009; Minkler, 2000; Nordenfelt, 2000; Schultz, Krieger & Galea, 2002). Community action is collective action undertaken by residents and community organizations to promote and protect the health and well-being of residents. It transforms an amorphous mass of people living in the same geographic space into a vibrant community, optimizing community resources (people, technology, natural resources, and supplies) in the service of its members’ health and well-being. Far too often, however, community actions are sporadic and disorganized, allowing for the involuntary fostering upon the community of health needs and priorities by outside agencies (both public and private). Neither sporadic, community-driven action nor well organized ones that are foisted from outside are likely to yield positive, sustainable results. Close collaboration between the participating organizations and the communities in all project activities, including the identification of health needs and the supports for them using a community participatory approach (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2003), likely translates public health policies into actual health-positive outcome communities.

Three qualities make for sustainable community-focused health services: locality orientation, organization of action, and planning of action. Locality orientation refers to the degree to which action is oriented to the local health needs and demand of the services to address those needs. Locally oriented action addresses a range of interests that the action fulfills (physical, psychological, and social well-being), as well as who are the participants (sponsors, actors, and beneficiaries) of the action in the context of the lived environment. Organization of action refers to the effectiveness and sustainability of a community health action inclusive of health awareness by members of the community and their capacity or willingness to address perceived health needs or demand services for them. Planning the health action involves consultative goal setting with participant organizations (or civic infrastructure for health) as well as planning the implementation and evaluation of the health actions. With

Who ICF Person’s Environment as Community

The

The

The Nature and Significance of COHS

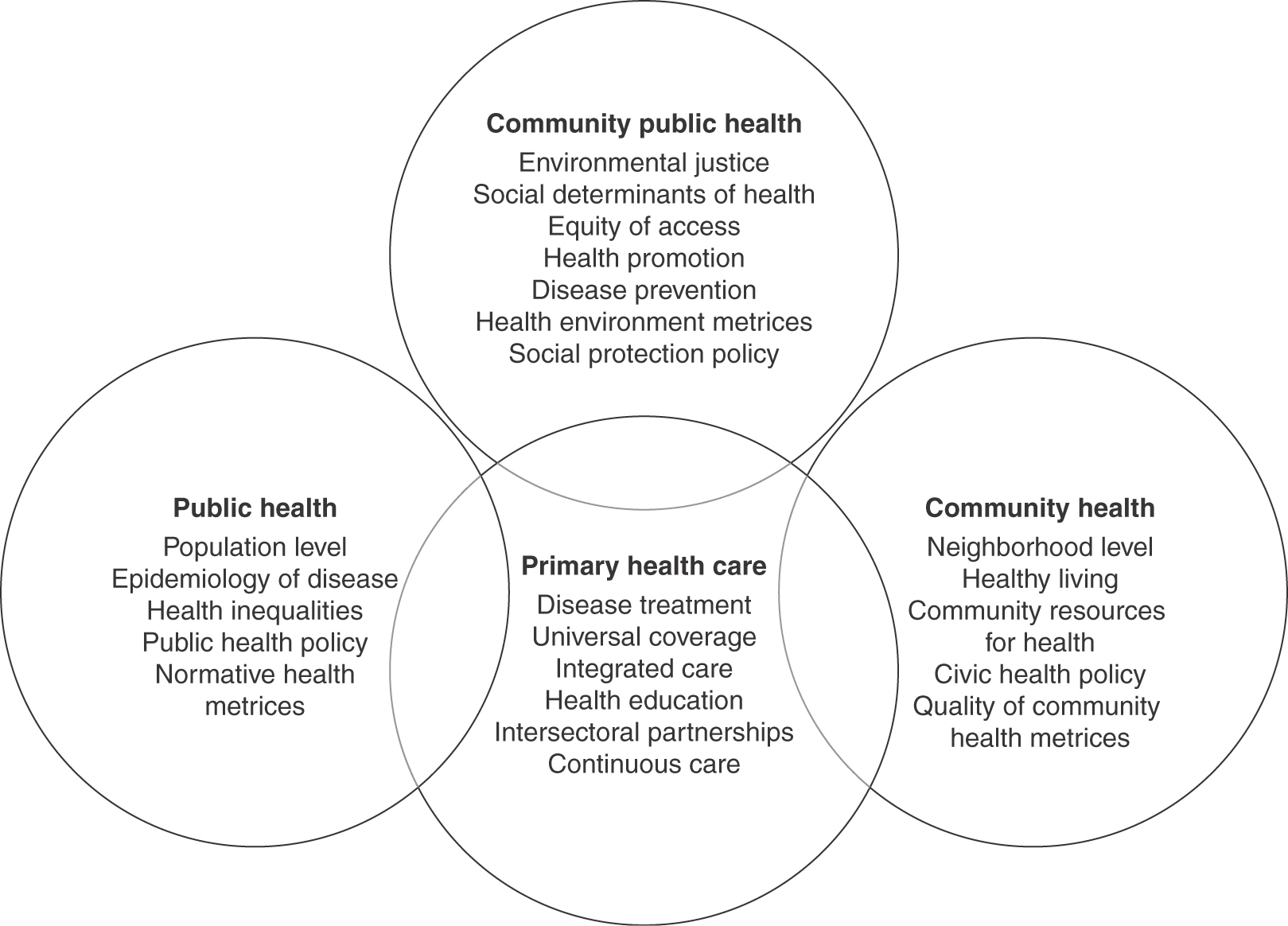

Health needs and services at the community level are characterized by complexity in access to care, use patterns and policies (see An, Huang, & Baghbanian, this volume). To address this complexity, current approaches to

While clinical medicine has in recent years become more inclusive in seeking to provide coordinated or integrated multidisciplinary care services (including behavioral medicine) to be more responsive to patient communities (Fisher & Dickinson, 2014; Institute of Medicine [

Clinical medicine services are comparatively well-funded than typical community health care services (Taylor & George, 2014;

Primary Health Care Services

Public Health

Historically, public health emerged from the realization that disease prevention and health promotion were as important to universal health care as interventions to mitigate diseases after they have occurred in populations. They have a focus on population-level data on the epidemiology of diseases and also on studying the effectiveness of large-scale interventions to prevent or treat diseases or to propose and implement strategies to reduce health disparities from social determinants of health. As previously noted, health disparities disproportionally affect minority status groups based on low income or race/ethnicity with a history of marginalization, females, gay–lesbian identity disability status, geographic location, or some combination of these (see Lopez Levers & Biggs; Williams & Ronan, this volume). Public health interventions seek to create health equity by mitigating the effects of health disparities, if not to reduce or eliminate the health disparities, by implementing policies to address modifiable social determinants of health. Health equity occurs when individuals and communities have similar opportunities to live a satisfying life free from preventable or avoidable negative social influences (see Bickenbach, this volume).

Community health workers (

Community Health Services

Community health services have the pursuit of health as the overarching goal rather than disease prevention per se. These typically seek to build community assets for health at the neighborhood level to support meaningful community engagement or involvement. They are designed to have multiplier effects on health-related outcomes from empowering community citizens to make healthy lifestyle choices. The most effective of community health interventions are raising the standard of living of community members through various community-friendly initiatives that address basic life sustenance issues such as the provision of sanitation and water supply services, affordable housing, transportation, employment, safe open spaces for exercise, recreation parks, and healthy food markets (Dluhy & Swartz, 2006; Taylor & George, 2014). Raising the standard of living as a tool for health promotion appears to achieve its effects by reducing risk for infectious diseases, preventing diseases associated with poverty, affording community citizens a sense of control over their lives, or reducing stress from the vagaries of meeting basic subsistence or personal safety. As an example of the effects of the lived environment on health and well-being of community members, affordable housing plays a critical role in the health and well-being of a community, yet is out of reach for more people on low income in both developing and developed countries. Many community residents on low income live with “housing stress,” which is when they pay much of their earnings for their housing, which leaves little to spend on decent food, health care, and education (Burke & Pinnegar, 2007). For instance, in 2007, about 80,000 low-income Australians paid more than 50% of their income on rent (Donald, 2007; see also Williams & Ronan, this volume). Public welfare housing supports in the form of tax benefit, public housing, and rental assistance are community-oriented interventions likely to positively impact the effects of housing stress and make way for healthier communities. Communities with physical infrastructure barriers such a major highway that cut through the neighborhood had lowered sense of wellbeing from risks for motor-vehicle accidents and reduced access from social services across the divide (Mindell & Karlson, 2012; see also Harley et al., this volume). The health benefits from interventions to modify environmental factors that impact health and well-being are likely with the participation of local community coalitions with a stake to promote intersectoral collaboration with other sectors, such as employment, education, and rural or urban planning (

Local communities have lived experience of needs, priorities, and aspirations that nonresident professionals have not. Supporting civic infrastructure for community competence (Cottrell, 1976) such as community coalitions for health (Butterfoss et al., 1993) contributes to sense of control by community members and indirectly to health and well-being. For instance, quality of family life, which is important for disease prevention and mitigation, is enhanced with resources health and wellbeing. Local communities with strong coalitions for health have pro-civic health policies or those that consider health and well-being integral to all community initiatives or activities.

Community Public Health

Community public health is emergent from the interface of public and community health services in the context of environmental and social justice. It focuses on interventions to promote health and well-being and prevent disease from environmental hazards, as well as noninfectious and nonoccupational environmental and social factors. Environmental hazards could be physical, chemical, and biological agents from industrial processes, and particularly the waste or emissions resulting. It also addresses health care access inequities that may result from social determinants of health. Social determinants of health include food supply, housing, economic and social relationships, transportation, education, and access to health care. They are life-enhancing resources, and their distribution between and within communities may vary with demographics of gender, education, race/culture, geographic location, and so on. They influence health-related quality of life and are often the targets for modification by community public health interventions.

Community coalitions typically work with public health policy makers and health care providers to translate public health policy into real community health benefits (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.). Community public health uses environmental health metrics (see Frumkin, this volume) and equity of health measures to index the quality of community health. Consequently, community public health prioritizes social protection policies across community sectors in the utilization of community resources for health (see also An et al., this volume; Comans, Turkstra, & Scuffham, this volume; Wagner, Austin, & Von Orff, 1996), targeting the most common preventable diseases from environmental and social inequalities, equity in health within communities, and intervening to change conditions that lead to disease (Brennan, Baker, & Metzler, 2008).

Summary and Conclusion

References

- Adewunmi, A. (2002). Community psychiatry in Nigeria. Psychiatric Bulletin, 26, 394–395.

- AHURI. (2009). National Housing Research Program. Research Agenda.

- Asuni, T. (1967). Aro hospital in perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry, 124, 71–78.

- Brennan Ramirez, L. K., Baker, E. A., & Metzler, M. (2008). Promoting health equity: A resource to help communities address social determinants of health. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Burke, T., & Pinnegar, S. (2007). Experiencing the housing affordability problem: Blocked aspirations, trade-offs and financial hardships. (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute: AHURI Research Paper No. 9). Melbourne, Victoria: Australia.

- Butterfoss, F. D., & Kegler, M. C. (2009). The community coalition action theory. In R. J. DiClemente,, R. A. Crosby, & M. C. Kegler (Eds.), Promoting equity: A resource to help communities address social determinants of health (pp. 237–276). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley.

- Butterfoss, F. D., Goodman, R. M., & Wandersman, A. (1993). Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion. Health Education Research, 8(3), 315–330.

- Campbell, C., & Jovchelovitch, S. (2000). Health, community, and development: Towards a social psychology of participation. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 10, 255–270.

- Connor, E., & Mullan, F. (Eds.). (1983). Community-oriented primary care: New directions for health services delivery: Conference proceedings. National Academies.

- Cottrell, C. S. (1976). The competent community. In B. H. Kaplan,, R. N. Wilson, & A. H., Leighton (Eds.), Further explorations in social psychiatry (pp. 195–209). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Cueto, M. (2004). The origins of primary health care and selective primary health care. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 1864–1874.

- Dluhy, M., & Swartz, N. (2006). Connecting knowledge and policy: The promise of community indicators in the United States. Social Indicators Research, 79, 1–23.

- Donald, O. (2007). Housing policy issues: Challenges and opportunities. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Government.

- Fisher, L., & Dickinson, W. P. (2014). Psychology and primary care: New collaborations for providing effective care for adults with chronic health conditions. American Psychologist, 69(4), 355–363.

- Golden, S. D., & Earp, J. A. L. (2012). Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education and behavior health promotion. Health Education and Behavior, 39(3), 364–372.

- Harley, G. (1955). Definitions of community: Areas of agreement. Rural Sociology, 20, 111–125.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2012). Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2000). Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202.

- Jones, L., & Wells, K. (2007). Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in communityparticipatory partnered research. JAMA, 297, 407–410.

- Kamanda, A., Embleton, L., Ayuku, D., Atwoli, L., Gisore, P., Ayaya, S., … Braitstein, P. (2013). Harnessing the power of the grassroots to conduct public health research in sub-Saharan Africa: A case study from western Kenya in the adaptation of community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches. BMC Public Health, 13, 1–10.

- Kark, S. L. (1974). Epidemiology and community medicine. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Kark, S. L. (1981). The practice of community oriented primary health care. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Las Nueces, D., Hacker, K., DiGirolamo, A., & Hicks, L. S. (2012). A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Services Research, 47, 1363–1386.

- Lasker, R. D., & Weiss, E. S. (2003). Broadening participation in community problem solving: A multidiscplianry model to support collabotative practice and research. Journal of Urban Health, 80(1), 14–47.

- Longlett, S. K., Kruse, J. E., & Wesley, R. M. (2001). Community-oriented primary care: Critical assessment and implications for resident education. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 14, 141–147.

- MacQueen, K., McLellan, E., Metzger, D. S., Kegeles, S., Strauss, R., Scotti, R., … Trotter, S. (2001). What is community? An evidence based definition for participatory public health. American Journal of Public Health, 91(12), 1929–1938.

- Mendenhall, T. J., Harper, P. G., Henn, L., Rudser, K. D., & Schoeller, B. P. (2014). Community-based participatory research to decrease smoking prevalence in a high-risk young adult population: An evaluation of the students against nicotine and tobacco addiction (SANTA) project. Families, Systems, & Health, 32, 78–88.

- Mindell, J. S., & Karlson, S. (2012). Community severance and health: What do we actually know? Journal of Urban Health, 89(2), 232–246.

- Minkler, M. (2000). Using participatory action research to build healthy communities. Public Health Reports, 115, 191–197.

- Minkler, M. (2004). Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 31, 684–697.

- Minkler, M. (2005). Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health, 82, ii3–ii12.

- Mpofu, E. (Ed.). (2011). Counseling people of African ancestry. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Mpofu, E. (2006). Majority world health care traditions intersect indigenous and complementary and alternative medicine (Editorial for special issue on indigenous healing practices). International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 53, 375–379.

- Nordenfelt, L. (2000). Action, ability, and health. Essays in the philosophy of action and welfare. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

- Pazoki, R., Nabipour, I., Seyednezami, N., & Imami, S. R. (2007). Effects of a community-based healthy heart program on increasing healthy women’s physical activity: A randomized controlled trial guided by community-based participatory research (CBPR). BMC Public Health, 7, 216.

- Puertas, B., & Schlesser, M. (2001). Assessing community health among indigenous populations in Ecuador with a participatory approach: Implications for health reform. Journal of Community Health, 26, 133–147.

- Richards, R. W. (2001). Best practices in community-oriented health professions education: International exemplars. Education for Health, 14, 357–365.

- Schulz, A. J., Krieger, J., & Galea, S. (2002). Addressing social determinants of health: Community-based participatory approaches to research and practice. Health Education & Behavior, 29, 287–295.

- Shattell, M., Hamilton, D., Starr, S., Jenkins, C., & Hinderliter, N. (2008). Mental health service needs of a Latino population: A community-based participatory research project. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29, 351–370.

- Taylor, G., & George, S. (2014). Affordable health: The way forward. The International Journal of Human Rights, 2(2), 1–18.

- Tennent, L., Farrell, A., & Tayler, C. (2009). Social capital and sense of community: What do they mean for young children’s success at school? Brisbane, Australia: Queensland University of Technology. Retrieved from http://www.aare.edu.au/05pap/ten05115.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Community action for environmental public health. Retrieved on July 3, 2014, from http://www.epa.gov/communityhealth

- Viswanathan, M., Ammerman, A., Eng, E., Gartlehner, G., Lohr, K. N., Griffith, D., … Whitener, L. (2004). Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. [Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 99.]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Wagner, E. H., Austin, B. T., & Von Korff, M. (1996). Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly, 74, 511–544.

- Wallerstein, N. (1992). Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: Implications for health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion, 6, 197–205.

- White, G. W., Suchowierska, M., & Campbell, M. (2004). Developing and systematically implementing participatory action research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85, 3–12.

- Wilkinson, K. (1991). The community in rural America. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (1946). WHO definition of Health. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, NY, June, 19–22.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata, 1978. Retrieved December, 2013. from http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/policy-documents/declaration-of-alma-ata,-1978

- World Health Organization (WHO). (1979). Report of the first meeting of the network of community oriented educational institutions, Kingston, Jamaica, June, 4–8.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (1986). A discussion document on the concept of and principles of health promotion. Health Promotion, 1, 73–78.

- World Health Organization (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2008). Integrated health services – What and Why? Technical Brief N.1. Retrieved October 13, 2014. from http://www.who.int/healthsystems/service_delivery_techbrief1.pdf