Research Article

Abstract

This study evaluated a multicomponent phase–based trauma treatment approach for 34 children who were victims of severe interpersonal trauma (e.g., rape, sexual abuse, physical and emotional violence, neglect, abandonment). The children attended a week-long residential psychological recovery camp, which provided resource building experiences, the Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Integrative Group Treatment Protocol (EMDR-IGTP), and one-on-one EMDR intervention for the resolution of traumatic memories. The individual EMDR sessions were provided for 26 children who still had some distress about their targeted memory following the EMDR-IGTP. Results showed significant improvement for all the participants on the Child’s Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale (CRTES) and the Short PTSD Rating Interview (SPRINT), with treatment results maintained at follow-up. More research is needed to assess the EMDR-IGTP and the one-on-one EMDR intervention effects as part of a multimodal approach with children who have suffered severe interpersonal trauma.

Violence against children is multidimensional and calls for a multifaceted response. Protection of children from violence is a matter of urgency. Children have suffered adult violence unseen and unheard for centuries. Children must be provided with the effective prevention and protection to which they have an unqualified right (United Nations, 2006).

Interpersonal violence, whether experienced directly or indirectly, especially during childhood, can either precipitate the onset of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or act as a risk factor that later increases the odds of developing PTSD after subsequent traumas (Brewing, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000).

Children whose traumas occur within interpersonal relationships may develop the associated symptoms of PTSD (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). These include difficulties with trust, affect regulation, somatic problems, impulse control, and identity. Children who have been abused often develop additional symptoms related to self-efficacy and sexuality (Van der Kolk, 2002).

Extensive maltreatment in childhood is associated with various biological effects that alter neurological development (De Bellis & Van Dillen, 2005). These biological diatheses set the stage for emotion processing and executive functioning deficits that lead to impaired self-regulation and later psychiatric disorders such as PTSD, depression, and other emotional problems (Van der Kolk, 2005). Research into PTSD among youth who are maltreated has burgeoned because of the substantial prevalence of the disorder among this group (Pecora, White, Jackson, & Wiggins, 2009).

Treatment of Children Who Are Abused

A multicomponent phase–based trauma treatment approach for the treatment of complex traumatic stress is strongly recommended (e.g., Courtois & Ford, 2009). The first phase of treatment focuses on patient safety, symptom stabilization, and improvement in basic life competencies. The second phase includes the exploration of traumatic memories by first reducing acute emotional distress resulting from the memories and then reappraising their meaning and integrating them into a coherent and positive identity.

The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) conducted an expert clinician survey on best practices for the treatment of complex PTSD (Cloitre et al., 2011). For first-phase approaches, emotion focused and emotion regulation strategies received the highest ratings in effectiveness, whereas education about trauma and mindfulness received top second-line rating. For second-phase approaches, the use of individual therapy was identified as a first-line approach for the processing of trauma memories, and group work combined with individual therapy received a top second-line rating.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is recommended for the treatment of PTSD in both adults and children by numerous international guidelines such as the Cochrane Review (Bisson & Andrew, 2007) and the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2005). There is also preliminary support for its application in the treatment of other psychiatric disorders, for various mental health problems, and somatic symptoms.

The theoretical frame on which EMDR is based is the adaptive information processing (AIP) model. Shapiro (2001) posits that much of psychopathology is caused by the maladaptive encoding of incomplete processing of traumatic and/or disturbing adverse life experiences. This is thought to impair the individual’s ability to integrate these experiences in an adaptive manner. The eight-phase, three-pronged process of EMDR is said to facilitate the resumption of normal information processing and integration. This treatment approach, which targets past experience, current triggers, and future potential challenges, can often result in the alleviation of presenting symptoms, with a decrease or elimination of distress related to the disturbing memory, improved view of the self, relief from bodily disturbance, and resolution of present and future anticipated triggers. The evolution and elucidation of both neurobiological mechanisms (unknown for any form of psychotherapy) and theoretical models are ongoing through research and theory development (EMDR International Association [EMDRIA], 2011).

There is a body of research evaluating EMDR treatment of Type 1 (single incident) traumas in children: natural disaster (Chemtob, Nakashima, & Carlson, 2002; Fernandez, 2007; Greenwald, 1994), burglary (Cocco & Sharpe, 1993), and road traffic accidents (Kemp, Drummond, & McDermott, 2010; Ribchester, Yule, & Duncan, 2010). Individual EMDR with children who are traumatized has been found to be very effective in reducing symptoms of posttraumatic stress. See Adler-Tapia and Settle (2008) and Fleming (2012) for reviews.

There are only a few studies that have specifically investigated EMDR treatment of Type 2 (enduring experiences such as sexual abuse or war) traumas in children (Fleming, 2012). A randomized controlled trial by Jaberghaderi, Greenwald, Rubin, Zands, and Dolatabadi (2004) assessed the provision of EMDR or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for 14 Iranian girls aged 12–13 years who are sexually abused. Although the girls had self-reported symptoms of trauma and teacher reported problem behaviors, no diagnostic assessment was conducted. Participants could receive up to 12 treatment sessions; there was a minimum of 10 sessions of CBT but no minimum for EMDR, and EMDR was significantly more efficient than CBT. Self-report, parent-report, and teacher-report measures were administered at pretreatment and 2 weeks posttreatment. There was no significant difference between treatments, and both EMDR and CBT produced large effect sizes on the posttraumatic symptom outcome and medium effect sizes for a decrease on classroom behavioral problems.

Wadda, Zaharim, and Alqashan (2010) evaluated the prevalence of PTSD in children who had immigrated to Malaysia to escape the Iraq war and found that 68.5% had PTSD symptoms. The parents of 12 children (aged 7–12 years) agreed to allow their children to receive 12 sessions of EMDR. There was no statistical difference at pretreatment in scores on the PTSD measure between the two groups of children, but at posttreatment, the scores for the EMDR group had decreased significantly.

The EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol

The EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol (EMDR-IGTP) was developed by members of Mexican Association for Mental Health Support in Crisis (AMAMECRISIS) when they were overwhelmed by the extensive need for mental health services after Hurricane Pauline ravaged the western coast of Mexico in 1997. This protocol is also variously known as the Group Butterfly Hug Protocol, the EMDR Group Protocol, and the Children’s EMDR Group Protocol. For detailed instructions and the scripted version, see Artigas, Jarero, Alcalá, & López Cano (2009). EMDR-IGTP has been used in its original format, or with adaptations, to meet the circumstances in numerous settings around the world (Gelbach & Davis, 2007; Maxfield, 2008). Case reports and field studies have documented its effectiveness with children and adults after natural or man-made disasters, during ongoing war trauma, and ongoing geopolitical crises (Adúriz, Knopfler, & Bluthgen, 2009; Jarero & Artigas 2009; Jarero & Artigas, 2010; Jarero, Artigas, & Hartung, 2006; Jarero, Artigas, Mauer, López Cano, & Alcalá, 1999; Jarero, Artigas, Montero, 2008; Zaghrout-Hodali, Alissa, & Dodgson, 2008). A new application for interpersonal trauma was tested in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where a field study showed that after two sessions of the EMDR Group Protocol, the 50 adult who are rape victims reported cessation of PTSD symptoms and lower back pain (Allon, as cited by Shapiro, 2011).

Innocence in Danger Organization

Innocence in Danger (IID; 2011) is a worldwide movement of child protection against sexual violence and exploitation. It is an international, nonprofit, and nongovernmental organization created by a group of citizens on April 15, 1999. Its goal is to implement the action plan of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Experts’ Meeting, convened in January of 1999, on sexual abuse of children, child pornography, and pedophilia on the Internet. IID working committees focus on increasing public awareness, through the media, of the increasing problems of pedophilia criminality and direct support of children who are abused, aged 0–18 years, through therapeutic and juridical procedures (IID, 2011).

IID operates in 29 countries throughout the world, with partners who share the same objectives. IID thus brings together militants, Internet specialists, jurists, political decision makers, businessmen, media, and national action groups. IID has bureaus in France, Switzerland, Germany, United States, England, and Colombia. Each bureau functions as an association in its country and it is economically independent from the others.

Since 2008, IID Colombia has been operating in Cali, a city in the southwest part of the country. The humanitarian mission of IID Colombia is to provide psychological support and treatment to child victims of violence and to advocate for the protection of all children by educating Colombian society about child mistreatment in all its forms. IID Colombia aims to be an organization specialized in the attention and prevention of traumas and posttraumatic stress generated by violence, particularly sexual violence, toward children and adolescents. It endeavors to include their families and to develop networks to help these intervention processes.

Prior to this study, IID Colombia, since its creation, had carried out three psychological recovery camps. Each camp lasted for 7 days, with children staying in dormitories in the city of Cali. The camps provided group treatment to about 35 children, aged 9–14 years who suffered various types of abuse. Treatment included group activities and EMDR. During the first three camps, procedures were implemented and tested, with modifications made to optimize the children’s experience. The promising results from these camps encouraged the authors to run a fourth camp as a research study.

Each camp lasted 7 days, with children staying either in dormitories in the city of Cali or with their families in different cities in the region. The total number of children treated in the three camps was of 70 (14 for the first, 24 for the second, and 32 for the third). Treatment included group activities and EMDR. These activities were focused mainly on body and language expressions, on experiencing their own emotions, and of their creative potential through art. During these three camps, procedures were implemented and tested with modifications. The promising results from these camps encouraged the authors to run a fourth camp as a research study.

Method

Participants

Thirty-four children (18 boys, 16 girls) aged between 9 and 14 years attended the camp. All had been victims of severe interpersonal violence (e.g., rape, sexual abuse, physical and emotional violence, neglect, abandonment); most (n = 32) were victims of rape or sexual abuse. One group (n = 19; 11 boys, 8 girls) of children came from an institution accredited by the Colombian Institute of Family Well-being (ICBF); these children had lived in the streets or had been removed from their families because of their own problematic behavior. The other group (n = 15; 7 boys, 8 girls) of children lived with their families and were victims of rape, sexual abuse, and physical and emotional violence. None of the children had had previous specialized psychological trauma treatment.

Procedure

The camp was conducted from December 1 through 7, 2011. The research was conducted in eight stages.

Stage 1: Previous to the camp’s commencement, the agency’s psychologist met individually with the children and a family/agency member to elaborate a clinical history of each child and to choose with the child the traumatic memory that would be reprocessed during the camp.

Stage 2: Before the camp commenced, the authors conducted a 1-day precamp retreat for the entire adult team (psychologists, social workers, and educational workers) preparing them for their work with the children during the camp.

Stage 3: During the camp (December 1–7, 2011), the children received a multicomponent phase–based trauma treatment approach. The pre-EMDR assessment was conducted on December 5, 2011 and EMDR group treatment was provided on December 5 and 6, 2011. Plans were made to provide individual EMDR to the 26 children whose subjective units of disturbance (SUD) for the specific trauma had not reached 0 during the group intervention.

Stage 4: Individual EMDR was provided during the camp on December 6 and 7, 2011 to six (from the 11 children who lived in institutions located out of the city of Cali) children whose SUD rating for the targeted trauma had not reached 0 during the group intervention. Two children received one individual EMDR session, and four children received two sessions.

Stage 5: Individual EMDR was provided after the camp between December 12 and 16, 2011 to the 20 children whose SUD rating for the targeted trauma had not reached 0 during the group intervention and who lived in Cali. Most of the children (n = 18) needed one individual session, and only two children needed two individual sessions. During this stage, the family psychoeducation intervention was done for 7 of the 15 children who were living at home and not in institution.

Stage 6: (December 19–23, 2011). The posttreatment assessment was administered.

Stage 7: (January 27 and February 3, 2012). The children participated in the “Journeys of Art and Internal Peace.” Children living in Cali (n = 23, children from the institution plus children from the families) attended the first day, and children from the institution outside of Cali (n = 11) attended the second day. These journeys consisted in a day of recreation, art, and mindfulness activities. The objective was for the children to continue the process of inner healing and psychological recovery, which had begun during the camp: practicing inner communication, being open to others, and socializing in an empathic way.

Stage 8: (February 8–10, 2012). The follow-up assessment was administered.

Measures

Test Administrations

The Short PTSD Rating Interview (SPRINT; Connor & Davidson, 2001; Vaishnavi, Payne, Connor, & Davidson, 2006) and the Child’s Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale (CRTES; Jones, 1997) were administered to the children (Stage 3) during the camp prior to provision of EMDR-IGTP and individual EMDR. These measures were also administered at posttreatment (Stage 6) and at follow-up (Stage 8). The testing was conducted by a clinical psychologist who experimented in the EMDR-IGTP. Ratings of SUD (Shapiro, 2001) were taken during the provision of EMDR-IGTP and EMDR, as described in the following text, to monitor the progress of treatment during the session.

Short PTSD Rating Interview

The SPRINT (Connor & Davidson, 2001; Vaishnavi et al., 2006) is an eight-item interview or self-rating questionnaire with solid psychometric properties that can serve as a reliable, valid, and homogeneous measurement of PTSD illness severity and global improvement as well as a measure of somatic distress; stress coping; and work, family, and social impairment. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (a little bit), 2 (moderately), 3 (quite a lot), and 4 (very much). Scores between 18 and 32 correspond to marked or severe PTSD symptoms, 11 and 17 to moderate symptoms, 7 and 10 to mild symptoms, and scores of 6 or less indicated either no or minimal symptoms. The SPRINT also contains two additional items to measure global improvement according to percentage change and severity rating. This questionnaire was translated from English to Spanish and from Spanish to English, reviewed, authorized by one of its authors, and adapted for children language. SPRINT performs similarly to the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) in the assessment of PTSD symptoms clusters and total scores and can be used as a diagnostic instrument (Vaishnavi et al., 2006). In the SPRINT, a cutoff score of 14 or more was found to carry a 95% sensitivity to detect PTSD and 96% specificity for ruling out the diagnosis, with an overall accuracy of correct assignment being 96% (Connor & Davidson, 2001).

Child’s Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale

The CRTES (Jones, 1997) was derived from the Impact of Events Scale (Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979). It is a 15-item self-report measure designed to assess psychological responses to stressful life events. Responses are scored according to a Likert scale, where 0 (not at all), 1 (rarely), 3(sometimes), and 5 (often). In addition to a total score, the CRTES provides scores for two subscales: intrusion and avoidance. Scores less than 9 are considered low distress; between 9 and 18, moderate distress; and 19 and over, high distress. Although it is a self-report measure, the questions were read aloud to the younger children by the Emotional Protection Team (EPT) members. Their responses were recorded by the EPT. This measure was administered to the children at pretreatment, at 1-week posttreatment, and at 3-month follow-up.

Subjective Units of Disturbance Scale

A modification of SUD (Shapiro, 2001; Wolpe, 1958) was used. Instead of asking the children to simply rate the level of their disturbance, they were shown a diagram that depicts faces representing different levels of negative emotion (from 0 to 10, where 0 shows no disturbance and 10 shows severe disturbance) and asked to select the face that best represented their emotion and to write the corresponding number on their picture. Children were assisted in this process by members of the psychological recovery camp team.

SUD scores are an integral part of EMDR treatment (Shapiro, 2001), and their use has been demonstrated in EMDR studies with adults who are traumatized. For example, the SUD scale was shown to have a good concordance with pre–post physiological autonomic measures of anxiety (e.g., Wilson, Silver, Covi, & Foster, 1996). Physiological dearousal and relaxation were related to a decrease in the SUD score at the end of a session (Sack, Lempa, Steinmetz, Lamprecht, & Hofmann, 2008), and the SUD was significantly correlated with posttreatment therapist-rated improvement (Kim, Bae, & Park, 2008).

Treatment

Precamp Workshop for Treatment Providers

Before the fourth camp—and research study—started, the authors conducted a workshop retreat to provide education about trauma therapy and EMDR treatment and theory for the entire adult team (psychologists, social workers, artists, and educational workers) who was going to participate in the camp. It was explained that in the treatment of traumatic complex memories, EMDR is understood as one component of an integrated treatment plan (Tinker & Wilson, 1999).

The focus pointed also toward the importance of reducing the overarousal of the sympathetic nervous system. The value of the camp activities was highlighted because they were designed to facilitate essential experiences of safety and stability (Courtois & Ford, 2009). Special attention was given to the team members always having a deep, loving, and respectful presence in the emotionally difficult moments (Jarero et al., 2008), and it was explained that this adult presence might increase children’s memory networks of positive information and could be a resource for the future. The workshop also provided education about the impact and treatment of trauma and reviewed emotion-focused and emotion regulation strategies (Servan-Schreiber, 2003) and mindfulness.

Overview of Treatment

A multicomponent phase–based trauma treatment approach was conducted during the camp. This approach for complex traumatic stress was recommended by Courtois and Ford (2009). The first phase of treatment focuses on patient safety, symptom stabilization, and improvement in basic life competencies. The second phase includes the exploration of traumatic memories by first reducing acute emotional distress resulting from the memories and then reappraising their meaning and integrating them into a coherent and positive identity.

Empirical studies that have included only those with complex trauma histories have found that memory processing is reasonably well tolerated and of benefit when conducted in a multicomponent fashion (e.g., Chard, 2005). There may be an advantage to integrating EMDR with other treatments when comorbid disorders or social issues also need to be targeted and may influence the treatment response (Fleming, 2012). Tufnell (2005) concluded that EMDR is suitable for use with children and adolescent with comorbid mental health problems when used in conjunction with other treatments.

In this study, the first phase of trauma therapy provided a range of different activities in the context of a therapeutic camp setting to develop stabilization and competencies. This research examined the effectiveness of the second phase of trauma therapy using a combination of group, EMDR-IGTP, and one-on-one EMDR intervention.

First Phase of Trauma Treatment

Please note that the first phase of trauma therapy corresponds to Phases 1 and 2 of standard EMDR and EMDR-IGTP procedures. This phase included the history taking session, which occurred for each child prior to the camp with the agency psychologist—and all of the experiences within the camp setting—from the children’s arrival on December 1 until December 7 when they left the camp.

The camp activities included the following: Children woke up early in the morning, practiced soft gymnastics and hatha yoga. The purpose of this was to support the processes of mental healing (Patanjali, 1991). Yoga practice has been used as an intervention for resolving traumatic stress because it facilitates increased positive mood, acceptance, and a peaceful stance through the care of body and the control of the breath (Van der Kolk, 2012). During each day, the children engaged in various activities and workshops. For example, one day, they visited the Gold Museum in Cali, Columbia, as an experience of participation in city life and for cultural exposure. Each night, before going to bed, the children had a party with stories, relaxation, slow and soft sound, and children’s music. Activities included the following:

1 The art in many expressions

Several art workshops were conducted by artists to help children get in touch with their creative potential. (a) In the painting workshop “Recovery of the child that I am,” the objective was for the children to find their “inner child” who is beyond pain and suffering and so to experience security and confidence (Tafurt, personal communication, July 3, 2011). (b) Two music workshops were conducted. In “Approach to the music catching the rhythm,” children were organized in groups to discover the concept of rhythm and create a collective pace. In “The music and my sensations, I create a story,” each child wrote a story inspired by his or her experience of the music (happiness, sadness, tenderness, mystery, etc.). (c) In the sculpture workshop, children encountered the clay as material, and then after listening to a story, each sculpted figures/shapes of the animals he or she liked and painted and decorated them. (d) In the theatre workshop, the children attended the theatrical presentation of the story Buddy the Dog’s EMDR (Meignant, 2007) so that they could understand the usefulness of the alternate stimulations. This workshop was given in the same day as, but prior to, the therapy EMDR-IGTP.

2 Physical activities

The children engaged in various sports and recreational activities. The therapeutic purposes were to achieve the known benefits of physical exercise, to improve social skills, and to help the children reconcile with their bodies and the world (Binswanger, 1971).

3 Practice of emotional regulation and harmonization

The aim of these practices was for the children to regulate their perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors to generate harmony in them. These practices were chosen from the following activities: (a) Stories and relaxation followed the recommendations of Lovett (1999) in which the story initially presents something positive to attracts the child’s attention, then describes a traumatic event and related symptoms, and then ends with resolution of the trauma and positive beliefs. (b) The children learned the practice of “mindfulness” (Williams, Teasdale, Segal, & Kabat-Zinn, 2007) to increase their direct experience of the body and to develop an attitude of compassion toward self (Nhat Hanh, 1974) as well as the cardiac coherence exercise (Deglon, 2006). (c) In the human values workshop, the children used imagery and cognitions to visualize a future full of possibilities, expressing deeply integrated human values. (d) Spiritual orientation was taught not from a religious orientation but with encouragement for each child to be caring toward self and others. (e) Psychotherapeutic biodynamic massages were provided to the children to enhance relaxation and to contribute to the children’s feeling of security inside their own body (Boyesen, 1985).

4 Specific preparation for EMDR

To prepare for EMDR, the children took part in a theatrical activity of “The dolphin and the doll Lupita” and learned the practice of abdominal breathing technique (ABT)—both activities described in the EMDR-IGTP for children (Jarero et al., 2008). The activities of creating their “safe place” and “normalizing the reactions” (whose aim is to recognize, to validate, and to normalize the signs and symptoms of the posttraumatic stress) were done as described in the EMDR-IGTP for children. Children were assisted by the treatment team in the learning and practicing the butterfly hug (Artigas, 2011) and completed the “exercise with the little faces”—a tool used with EMDR-IGTP for children to learn how to communicate their level of emotional disturbance and SUD.

Second Phase of Trauma Treatment

Please note that the second phase of trauma treatment corresponds to Phases 3–7 of EMDR therapy (Shapiro, 2001). In this study, we provided EMDR-IGTP to all 34 participants and individual EMDR therapy to 26 participants. The EMDR-IGTP was embedded into the camp activities. The individual EMDR sessions were provided for 7 out of town participants on the last day of the camp and for the other 20 children after completion of the camp activities. These therapies were administered according to the standard protocols (Artigas et al., 2009; Shapiro, 2001) by three therapists who were all EMDR-certified therapists and who all had training and experience working with children and vulnerable populations.

EMDR-IGTP.

The group therapy was administered to all 34 children in one group, and the treatment lasted for 6 hours. It was provided to all children in one group on three occasions over a 3-day period. On the first day, children completed preparation phase of EMDR-IGTP; on the second day, they did Phases 3–7 (first SUD measure); on the third day, they did again Phases 3–7 (second and last SUD measures).

The treatment was administered in the following manner: Each child was provided with colored crayons and with a sheet of blank paper, which they folded into four quarters. The children were asked to recall the traumatic event that they had selected when they met with the psychologist before the camp began and then were instructed to draw a picture representing the traumatic event incident in the top left quarter of the page. They were asked to provide a SUD rating for the incident and write the number on the picture. They were then instructed to look at their drawing while they performed the butterfly hug. After 3 minutes, the children were asked to observe how they felt and to draw whatever they wanted in the next quarter related to the event. This procedure was repeated for the four quarters. After that, the children were instructed to look at the drawing that was most disturbing and to write the SUD on the back of the paper. Next, the children were instructed to draw how they saw themselves in the future and to write a word, phrase, or a sentence that explains what they drew. After that, the children were instructed to remember the event, close their eyes, scan their body, and at the end do the butterfly hug for 3 minutes. In the last step, the children were instructed to go to the safe place and after 1 minute to breathe deeply and open their eyes.

Individual EMDR.

The individual treatment sessions each lasted for 60 minutes. The target of the session was the same incident that had been the focus of the group treatment. The pictures were used. In this administration, the children were also asked to identify a negative cognition. Treatment progressed following standard EMDR procedures.

Results

The strong effects of the EMDR-IGTP treatment are evident in the decreased SUD scores (see Figure 1). The children’s ratings of subjective disturbance dropped during the first session, with results maintained and a further reduction during the second session.

Changes in subjective units of disturbance (SUD) scores during Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Integrative Group Treatment Protocol (EMDR-IGTP) sessions.

The effects of the full program were measured using the CRTES and the SPRINT (Connor & Davidson, 2001; Vaishnavi et al., 2006) administered at pretreatment, posttreatment, and follow-up assessment in two groups of children (institution and family). Table 1 shows the mean scores and standard deviations obtained in both groups for each of the instruments applied across time.

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Follow-up | |||||

| Group | n | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| SPRINT | |||||||

| Institution | 19 | 18.95 | 6.786 | 4.53 | 3.657 | 2.11 | 2.726 |

| Family | 15 | 16.73 | 5.824 | 4.73 | 2.963 | 1.00 | 1.254 |

| Total | 34 | 17.97 | 6.384 | 4.62 | 3.321 | 1.62 | 2.243 |

| CRTES | |||||||

| Institution | 19 | 35.79 | 9.157 | 9.84 | 6.283 | 4.42 | 3.641 |

| Family | 15 | 35.13 | 7.945 | 5.80 | 3.489 | 2.33 | 2.289 |

| Total | 34 | 35.50 | 8.522 | 8.06 | 5.554 | 3.50 | 3.250 |

[i] Note. SPRINT = Short PTSD Rating Interview; CRTES = Child’s Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale.

Comparison of the Effect of the Treatment in the Two Different Groups

With the objective to figure out whether differences exist depending on the condition (family or institution), a general linear model was applied. The scores of both instruments (CRTES and SPRINT) were compared for the repeated measurements (pretreatment, posttreatment, and follow-up) for each of the groups (institution and family). The results did not show any significant effects for the interaction between scores of the instruments and the type of group. These results show that the treatment results followed a similar pattern for both groups (institution and family).

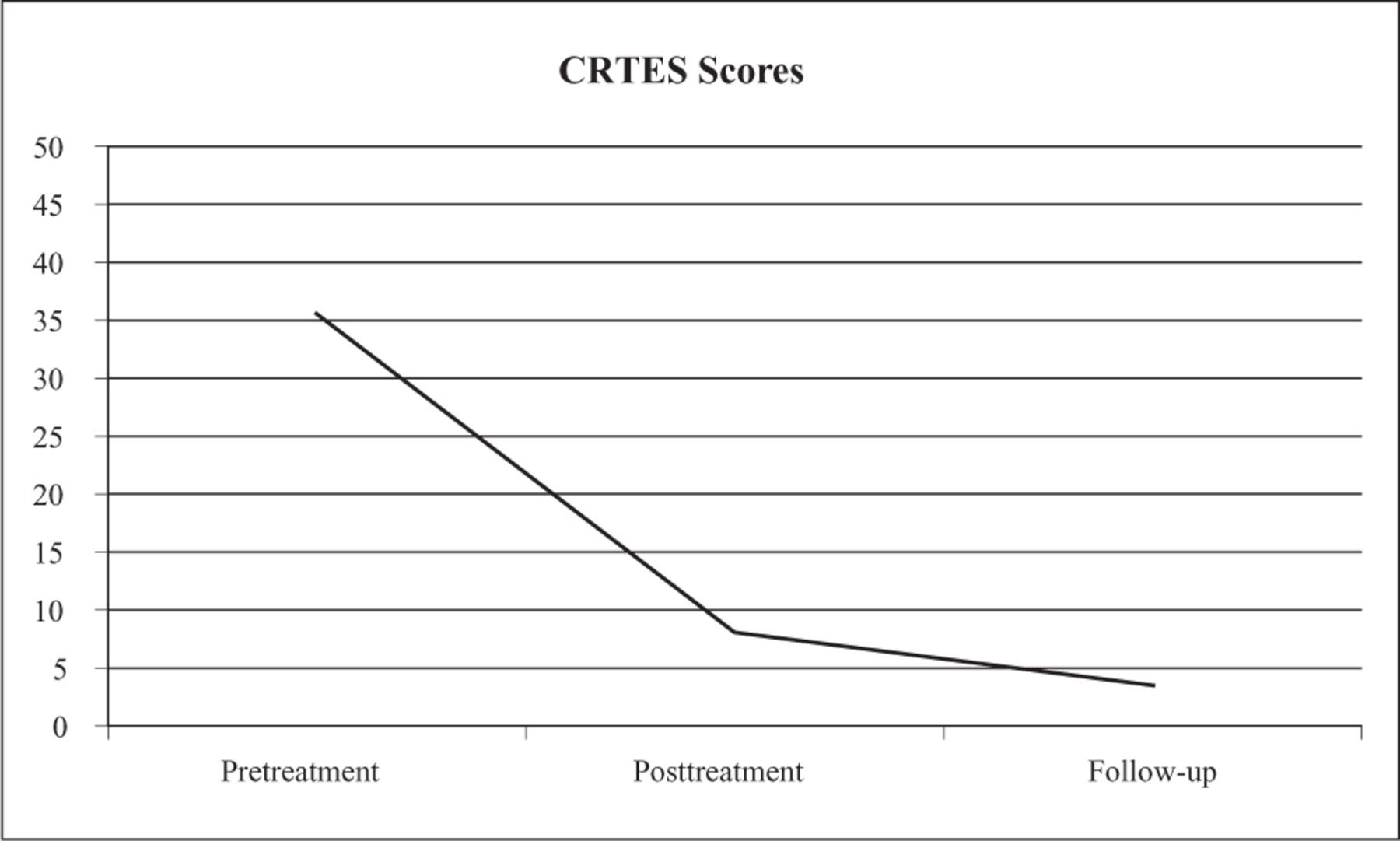

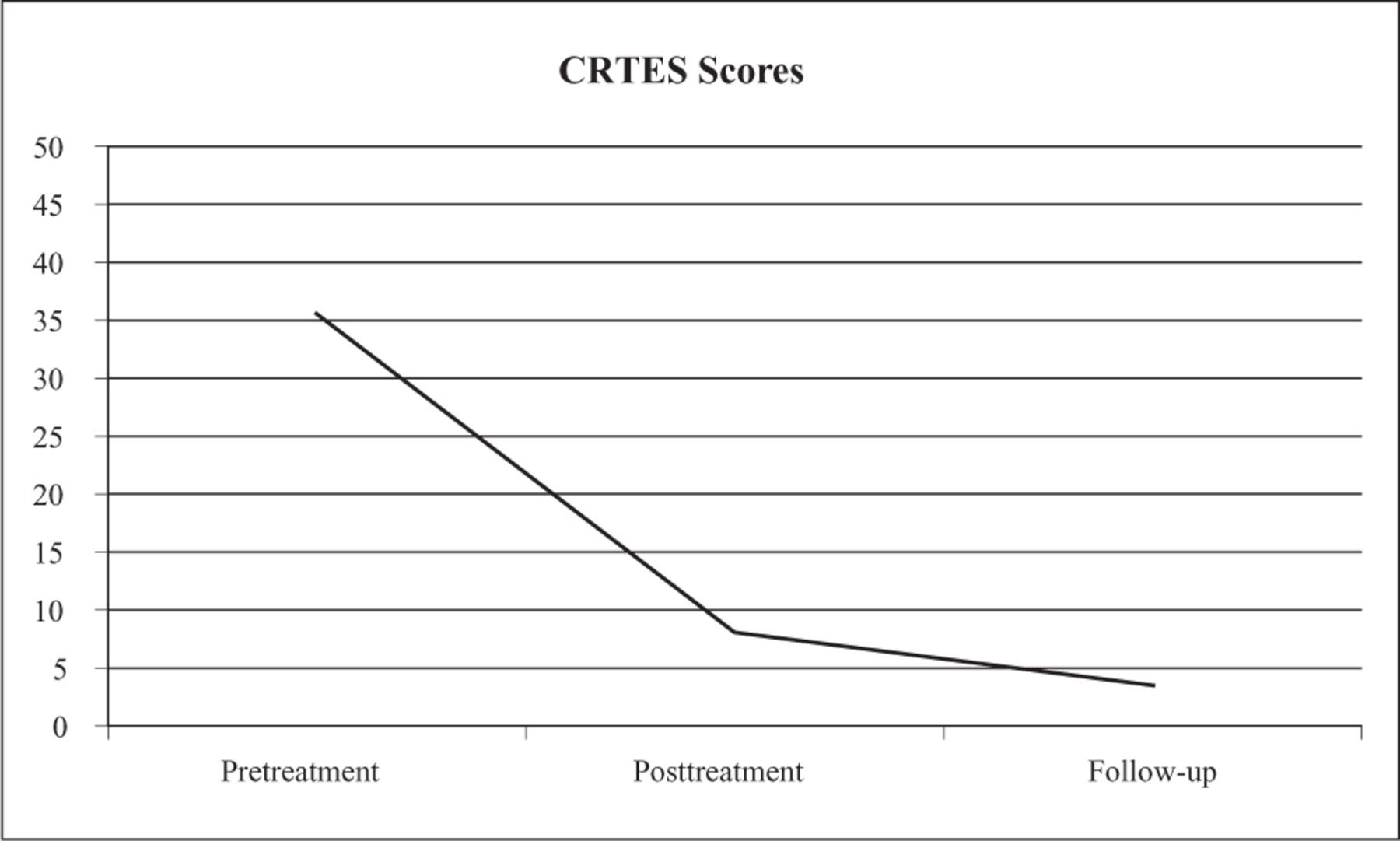

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a significant effect of time for both instruments, with all participants (N = 34) showing improvement on the CRTES (F[1, 33] = 520.26, p < .001) and SPRINT (F[1,33] = 259.27, p < .001). All the SPRINT scores at follow-up indicated minimal or mild PTSD symptoms (Figure 2). Also, all CRTES scores on the follow-up indicated low distress (Figure 3).

Changes in Short PTSD Rating Interview (SPRINT) scores following treatment.

Changes in Child’s Reaction To Traumatic Events Scale (CRTES) scores following treatment.

Planned post hoc t tests were conducted to evaluate change for the total group and each separate group. Significant reduction in symptoms was shown for CRTES (t[33] = 15.49, p < .001) and for SPRINT (t[33] = 19.87, p < .001; see Table 1 and Figures 2 and 3). These findings confirm the effect of the program and its maintenance throughout time. Finally, the rapid shift in SUD ratings during the processing sessions (Figure 1) is consistent with those reported in previous studies.

Global Improvement.

The SPRINT contains two items to measure global improvement, one assessing percentage change and the other rating severity. Item 1: “How much better do you feel since beginning treatment? As a percentage between 0 and 100.” Item 2: “How much has the above symptoms improved since starting treatment? 1 (worse), 2 (no change), 3 (minimally), 4 (much), 5 (very much).” On Item 1, the mean response at follow-up for the group of participants is 95% and, on Item 2, the mean response at follow-up was very much.

Follow-up Journeys of Art and Internal Peace.

Various children had expressed that they were looking forward to being together for the follow-up group sessions called “Journeys of Art and Internal Peace.” During the journeys (January 27 and February 3, 2012), the authors’ clinical observations were that children had a new sense of pleasure and a greater capacity to enjoy themselves and have fun.

Discussion

The obtained results show significant effects of the EMDR treatment in children regardless of the setting in which they were living either with their family or in an institution. The effects of the treatment were maintained over time as is shown in the follow-up measurement.

Multimodal Treatment

Multimodal treatment was provided to the children, with the first phase of therapy occurring in the context of a psychological camp setting. As described previously, the activities were designed to increase self-awareness and self-acceptance. The children learned emotion-focused and emotion regulation strategies as well as mindfulness. These practices have been evaluated by trauma experts as first- and second-line Phase 1 treatments (Cloitre et al., 2011). The multimodal therapy provided in this study addressed many of the children’s disparate therapeutic needs. This 1-week program appeared sufficient to enable preadolescent children suffering from complex trauma to experience significant change so that they could carry on with their lives with new feelings of strength and joy.

From an information processing theoretical perspective (Shapiro, 2001), the authors consider that one of the key benefits of the various activities was the creation and strengthening of positive memory networks. These networks were then available for access to children during EMDR processing of their traumatic memories. It is hypothesized that this allowed the children to focus on the memory without being submerged by emotional disturbances.

This study showed positive results from 1 week of multimodal treatment that included EMDR-IGTP and (for most of the children) one or two individual EMDR sessions. This was a very effective and time-limited treatment. Moreover, treating a large number of children in 1 week is advantageous in terms of costs.

This appears to be an efficient alternative to the type of treatment typically provided to children, which involves group or individual sessions extending over a 2- or 3-month period. Research has demonstrated that children with PTSD substantially improve in therapies lasting 9 and 12 weeks, and the ISTSS survey responses (Cloitre et al., 2011) suggested an even longer treatment course for complex PTSD. We recommend that multimodal treatment with EMDR-IGTP and individual EMDR be considered as a powerful alternative to traditional approaches.

EMDR and EMDR-IGTP

The results of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of a combination of EMDR-IGTP and individual EMDR in resolving PTSD symptoms for children who have experienced interpersonal trauma. The findings are consistent with those of other studies that have investigated the use of these approaches for children who are traumatized. However, the application of EMDR and EMDR-IGTP in this study was unique in several important ways.

The other studies of EMDR-IGTP found it to be an effective and efficient treatment for groups of individuals who have together experienced a specific disaster. In this study, the traumatic events, which were targeted by the children in their EMDR treatment, were individual events. Nevertheless, the group protocol was suitable and effective. It was provided on three occasions for these complex trauma participants, not as a single application as is the more common use in other studies (see Figure 1).

This is also the first study that measured the effects of the combination of EMDR-IGTP plus individual EMDR. It was observed that the three sessions of EMDR-IGTP had the effects of decreasing the SUD ratings associated with the traumatic memory and of increasing the child’s sense of mastery and confidence that they could cope with the terrifying memories. Only one or two individual EMDR sessions were needed by these children who had experienced various severe interpersonal traumas.

It should be noted that although only one memory was targeted, the effects generalized to the entire memory cluster of similar incidents (e.g., rape, sexual abuse, physical and emotional violence, neglect, abandonment). Shapiro (2001) mentioned that when the client chooses for reprocessing one incident that represent a particular cluster, “Clinical reports have verified that generalization will usually occur, causing a reprocessing effect throughout the entire cluster of incidents” (p. 207).

The results in this study suggest that the combination of EMDR-IGTP and EMDR may be a very potent therapeutic approach—one which could be used in various settings.

Recommendations

This program is suitable for such contexts as present-day Colombia. The end of conflicts and the construction of a lasting peace provide an opportunity to reestablish mental health in all individual victims of conflict. The authors propose to implement this program for all Colombian children who have been victims of severe interpersonal trauma.

To date, there are few studies exploring adaptations of, or alternatives to, established PTSD treatment developed specifically for individuals with complex trauma histories (Cloitre et al., 2011). The authors recommend future research on the use of EMDR as part of a multicomponent phase–based trauma treatment approach.

References

- R. L. Adler-Tapia, & C. S. Settle (2008). EMDR and the art of psychotherapy with children. New York, NY: Springer.

- M. E. Adúriz, C. Knopfler, & C. Bluthgen (2009). Helping child flood victims using group EMDR intervention in Argentina: Treatment outcome and gender differences. International Journal of Stress Management, 16(2), 138–153.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

- L. Artigas (2011). Escenas detrás de las alas del abrazo de la mariposa [Behind the scenes of the butterfly hug]. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicotraumatología y Disociación, 1(1), 1–10. Retrieved from http://revibapst.com/ARTICULO%20LUCY%202011.pdf

- L. Artigas, I. Jarero, N. Alcalá, & T. López Cano (2009). The EMDR integrative group treatment protocol (IGTP). In M. Luber (Ed.), Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) scripted protocols: Basic and special situations (pp. 279–288). New York, NY: Springer.

- L. Binswanger (1971). Introduction à l’analyse existentielle. Paris, France: Editions de Minuit.

- J. Bisson, & M. Andrew (2007). Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), CD003388. Retrieved from http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab003388.html

- G. Boyesen (1985). Entre psyché et soma. Paris, France: Payot.

- C. R. Brewing, B. Andrews, & J. D. Valentine (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 748–766.

- K. M. Chard (2005). An evaluation of cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 965–971.

- C. M. Chemtob, J. Nakashima, & J. G. Carlson (2002). Brief treatment for elementary school children with disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A field study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 99–112.

- M. Cloitre, C. A. Courtois, A. Charuvastra, R. Carapezza, B. C. Stolbach, & B. L. Green (2011). Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(6), 615–627.

- N. Cocco, & L. Sharpe (1993). An auditory variant of eye movement desensitization in a case of childhood posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 24(4), 373–377.

- K. M. Connor, & J. R. T. Davidson (2001). SPRINT: A brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(5), 279–284.

- C. A. Courtois, & J. D. Ford (2009). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- M. De Bellis, & T. Van Dillen (2005). Childhood post-traumatic stress disorder: An overview. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14,745–772.

- C. Deglon (2006). Les premiers pas avec la Cohérence Cardiaque. Paris, France: P. I. Conseil.

- EMDR International Association. (2011, September). Update EMDRIA definition of EMDR. EMDRIA Newsletter. Retrieved from http://www.emdria.org/associations/12049/files/SeptemberNewsletter2011.pdf

- I. Fernandez (2007). EMDR as treatment of post-traumatic reactions: A field study on child victims of an earthquake. Educational and Child Psychology, 24(1), 65–72.

- J. Fleming (2012). The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the treatment of traumatized children and youth. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 6(1), 16–26.

- R. Gelbach, & K. Davis (2007). Disaster response: EMDR and family systems therapy under communitywide stress. In F. Shapiro,F. W. Kaslow, & L. Maxfield (Eds.), Handbook of EMDR and family therapy processes (pp. 387–406). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- R. Greenwald (1994). Applying eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) to the treatment of traumatized children: Five case studies. Anxiety Disorders Practice Journal, 1, 83–97.

- M. Horowitz, N. Wilner, & W. Alvarez (1979). Impact of events scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41, 209–218.

- Innocence in Danger. (2011). Connaître IID. Retrieved from http://innocenceendanger.org/innocence-en-danger/organisation

- N. Jaberghaderi, R. Greenwald, A. Rubin, S. O. Zands, & S. Dolatabadi (2004). A comparison of CBT and EMDR for sexually-abused Iranian girls. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 11(5), 358–368.

- I. Jarero, & L. Artigas (2009). EMDR integrative group treatment protocol. Journal of EMDR Practice & Research, 3(4), 287–288.

- I. Jarero, & L. Artigas (2010). EMDR integrative group treatment protocol: Application with adults during ongoing geopolitical crisis. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 4(4), 148–155.

- I. Jarero, L. Artigas, & J. Hartung (2006). EMDR integrative treatment protocol: A post-disaster trauma intervention for children & adults. Traumatology, 12, 121–129.

- I. Jarero, L. Artigas, M. Mauer, T. López Cano, & N. Alcalá (1999, November). Children’s post traumatic stress after natural disasters: Integrative treatment protocol. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, Miami, FL.

- I. Jarero, L. Artigas, & M. Montero (2008). The EMDR integrative group treatment protocol: Application with child victims of a mass disaster. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 2, 97–105.

- R. Jones (1997). Child’s reaction to traumatic events scale (CRTES) . In J. Wilson & T. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- M. Kemp, P. Drummond, & B. McDermott (2010). A wait-list controlled pilot study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for children with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms from motor vehicle accidents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(1), 5–25.

- E. Kim, H. Bae, & Y. C. Park (2008). Validity of the subjective units of disturbance scale (SUDS) in EMDR. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 1, 57–62.

- J. Lovett (1999). Small wonders, healing childhood trauma with EMDR. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- L. Maxfield (2008). EMDR treatment of recent events and community disasters. Journal of EMDR Practice & Research, 2(2), 74–78.

- I. Meignant (2007). L’EMDR de Bouba le chien. Paris, France: Editions Maignant.

- T. Nhat Hanh (1974). The miracle of being awake. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2005). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. National clinical practice guideline number 26. Wiltshire, United Kingdom: Cromwell Press Limited.

- L. Parnell (1999). EMDR in the treatment of adults abused as children. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

- S. Patanjali (1991). Yoga sutras. In J. H. Woods (Ed.), Yoga sutras de Patanjali (p. 29). Paris, France: Albin Michel.

- P. J. Pecora, C. R. White, L. J. Jackson, & T. Wiggins (2009). Mental health of current and former recipients of foster care: A review of recent studies in the USA. Child and Family Social Work, 14, 132–146.

- T. Ribchester, W. Yule, & A. Duncan (2010). EMDR for childhood PTSD after road traffic accidents: Attentional, memory, and attributional processes. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 4(4), 138–147.

- M. Sack, W. Lempa, A. Steinmetz, F. Lamprecht, & A. Hoffmann (2008). Alteration in autonomic tone during trauma exposure using eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR)-results of a preliminary investigation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(7), 1264–1271.

- D. Servan-Schreiber (2003). Guérir, le stress, l’anxiété et la dépression sans médicaments ni psychanalyse. Paris, France: Editions Robert Laffont.

- F. Shapiro (2001). Eye movements desensitization and reprocessing. Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- F. Shapiro (2011, September). EMDR therapy update: Theory, research and practice. Paper presented at the EMDR International Association Conference in Anaheim, CA.

- R. H. Tinker, & S. Wilson (1999). Through the eyes of a child, EMDR with children. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

- G. Tufnell (2005). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the treatment of pre-adolescent children with post-traumatic symptoms. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10(4), 587–600.

- United Nations. (2006). Report of the independent expert Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro for the United Nations study on violence against children. Retrieved from http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/491/05/PDF/N0649105.pdf?OpenElement

- B. A. Van der Kolk (2002). Assessment and treatment of complex PTSD. In R. Yehuda (Ed.), Treating trauma survivors with PTSD (pp. 127–153). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric.

- B. A. Van der Kolk (2005). Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals, 35, 401–408.

- B. A. Van der Kolk (2012, June). Trauma in different mental disorders. Paper presented at the 13th Conference EMDR Europe, Madrid, Spain.

- S. Vaishnavi, V. Payne, K. Connor, & J. R. Davidson (2006). A comparison of the SPRINT and CAPS assessment scales for posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 23(7), 437–440.

- N. N. Wadda, N. M. Zaharim, & H. F. Alqashan (2010). The use of EMDR in treatment of traumatized Iraqi children. Digest of Middle East Studies, 19(1), 26–36.

- M. Williams, J. Teasdale, Z. Segal, & J. Kabat-Zinn (2007). Méditer pour ne pas déprimer. Paris, France: Editions Odile Jacob.

- D. L. Wilson, S. M. Silver, W. G. Covi, & S. Foster (1996). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Effectiveness and autonomic correlates. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 27(3), 219–229.

- J. Wolpe (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- M. Zaghrout-Hodali, F. Alissa, & P. Dodgson (2008). Building resilience and dismantling fear: EMDR group protocol with children in an area of ongoing trauma. Journal of EMDR Practice & Research, 2(2), 106–113.

Acknowledgments. The authors want to thank Dr. Martha Givaudan for her contribution to the data analysis of this work.

Figures

Changes in subjective units of disturbance (SUD) scores during Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Integrative Group Treatment Protocol (EMDR-IGTP) sessions.

View in Context

View in ContextChanges in Child’s Reaction To Traumatic Events Scale (CRTES) scores following treatment.

View in Context

View in ContextTables

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Follow-up | |||||

| Group | n | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| SPRINT | |||||||

| Institution | 19 | 18.95 | 6.786 | 4.53 | 3.657 | 2.11 | 2.726 |

| Family | 15 | 16.73 | 5.824 | 4.73 | 2.963 | 1.00 | 1.254 |

| Total | 34 | 17.97 | 6.384 | 4.62 | 3.321 | 1.62 | 2.243 |

| CRTES | |||||||

| Institution | 19 | 35.79 | 9.157 | 9.84 | 6.283 | 4.42 | 3.641 |

| Family | 15 | 35.13 | 7.945 | 5.80 | 3.489 | 2.33 | 2.289 |

| Total | 34 | 35.50 | 8.522 | 8.06 | 5.554 | 3.50 | 3.250 |

[i] Note. SPRINT = Short PTSD Rating Interview; CRTES = Child’s Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale.

| Period | Abstract | Full | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apr 2024 | 54 | 20 | 9 | 83 |

| Mar 2024 | 65 | 27 | 19 | 111 |

| Feb 2024 | 57 | 37 | 8 | 102 |

| Jan 2024 | 62 | 21 | 16 | 99 |

| Dec 2023 | 58 | 22 | 12 | 92 |

| Nov 2023 | 53 | 22 | 13 | 88 |

| Oct 2023 | 47 | 19 | 19 | 85 |

| Sep 2023 | 53 | 24 | 13 | 90 |

| Aug 2023 | 45 | 14 | 10 | 69 |

| Jul 2023 | 70 | 29 | 13 | 112 |

| Jun 2023 | 41 | 31 | 14 | 86 |

| May 2023 | 67 | 28 | 18 | 113 |

| Apr 2023 | 52 | 16 | 9 | 77 |

| Mar 2023 | 71 | 26 | 11 | 108 |

| Feb 2023 | 72 | 16 | 12 | 100 |

| Jan 2023 | 44 | 40 | 19 | 103 |

| Dec 2022 | 55 | 12 | 11 | 78 |

| Nov 2022 | 115 | 58 | 12 | 185 |

| Oct 2022 | 72 | 34 | 20 | 126 |

| Sep 2022 | 45 | 21 | 7 | 73 |

| Aug 2022 | 33 | 19 | 10 | 62 |

| Jul 2022 | 57 | 11 | 15 | 83 |

| Jun 2022 | 63 | 6 | 11 | 80 |

| May 2022 | 45 | 14 | 9 | 68 |

| Apr 2022 | 44 | 13 | 14 | 71 |

| Mar 2022 | 69 | 12 | 10 | 91 |

| Feb 2022 | 41 | 13 | 11 | 65 |

| Jan 2022 | 61 | 22 | 14 | 97 |

| Dec 2021 | 45 | 27 | 14 | 86 |

| Nov 2021 | 47 | 18 | 15 | 80 |

| Oct 2021 | 43 | 11 | 8 | 62 |

| Sep 2021 | 38 | 22 | 7 | 67 |

| Aug 2021 | 48 | 8 | 8 | 64 |

| Jul 2021 | 21 | 17 | 3 | 41 |

| Jun 2021 | 44 | 22 | 2 | 68 |

| May 2021 | 40 | 32 | 8 | 80 |

| Apr 2021 | 57 | 31 | 8 | 96 |

| Mar 2021 | 90 | 53 | 12 | 155 |

| Feb 2021 | 43 | 50 | 20 | 113 |

| Jan 2021 | 44 | 23 | 6 | 73 |

| Dec 2020 | 73 | 33 | 7 | 113 |

| Nov 2020 | 66 | 34 | 5 | 105 |

| Oct 2020 | 52 | 45 | 22 | 119 |

| Sep 2020 | 48 | 23 | 6 | 77 |

| Aug 2020 | 54 | 22 | 8 | 84 |

| Jul 2020 | 30 | 33 | 5 | 68 |

| Jun 2020 | 58 | 24 | 6 | 88 |

| May 2020 | 51 | 41 | 17 | 109 |

| Apr 2020 | 36 | 41 | 18 | 95 |

| Mar 2020 | 63 | 52 | 19 | 134 |

| Feb 2020 | 49 | 45 | 23 | 117 |

| Jan 2020 | 45 | 35 | 13 | 93 |

| Dec 2019 | 37 | 21 | 7 | 65 |

| Nov 2019 | 46 | 53 | 21 | 120 |

| Oct 2019 | 38 | 29 | 9 | 76 |

| Sep 2019 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 25 |

| Aug 2019 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 24 |

| Jul 2019 | 7 | 26 | 8 | 41 |

| Jun 2019 | 12 | 14 | 27 | 53 |

| May 2019 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 25 |

| Apr 2019 | 16 | 41 | 20 | 77 |

| Mar 2019 | 22 | 20 | 19 | 61 |

| Feb 2019 | 27 | 15 | 7 | 49 |

| Jan 2019 | 21 | 3 | 1 | 25 |

| Dec 2018 | 14 | 46 | 9 | 69 |

| Nov 2018 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Oct 2018 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 25 |

| Sep 2018 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Aug 2018 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 15 |

| Jul 2018 | 23 | 3 | 2 | 28 |

| Jun 2018 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |